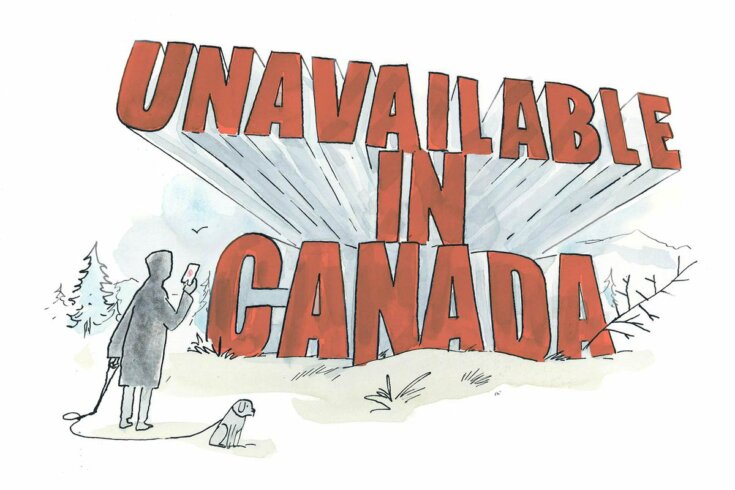

If you’re in Canada and have recently tried to share one of our articles on Facebook or check us out on Instagram, you’ve probably run into a small problem: you can’t.

The Online News Act (also known as Bill C-18), signed into law in June, is designed to force tech giants to pay for the journalism distributed on their platforms. The premise is that news outlets in Canada have lost significant ad revenue to these internet companies and deserve to be compensated. The companies don’t quite see it that way, saying the traffic referral they provide has been a boon to the journalism industry. To comply with the legislation, Meta, Facebook and Instagram’s parent company, has started blocking news content from social feeds in Canada. Had Google followed suit, it would have removed links to Canadian news sites from domestic search results. With the law set to go into effect by December, the possibility of a world where millions of Canadians would struggle to access reporting online—whether it was about a historic election in Manitoba, a storm flattening homes on the East Coast, or Taylor Swift’s new beau—became, for a period, real.

The standoff between the Liberal government and two of the world’s biggest digital platforms has prompted us to reflect on The Walrus’s relationship with big tech. There is no question that Meta and Google have helped us build our audiences here and around the world in unprecedented ways, including through partnerships and sponsorships. Many readers learn about our stories through aggregators, search engines, and social media links, and we are grateful for the reach and engagement they’ve provided. Yet those same channels can be taken from us on a whim. There is an expression often used to capture the power of the press: never pick a fight with someone who buys ink by the barrel. Today the ink is barrelled inside algorithms we don’t own.

Digital platforms are still too important to our work for us to completely unfriend them, and so we encourage readers to follow us on Substack, X (formerly Twitter), LinkedIn, and TikTok. But our dependence on tech companies has kicked off an organization-wide debate about how we might better diversify the ways in which readers find our award-winning content. We are putting more resources into our popular newsletter, where we round up the week’s stories and which you can sign up for on our website. And while you’re there, I would urge you to bookmark thewalrus.ca on your browser so you can keep pace with the breadth and quality of our reporting. And don’t forget that The Walrus still has a thriving analogue side that isn’t at the mercy of algorithms: our print edition. If you’re already a subscriber, we would love it if you gave a subscription to a friend.

The really scary long-term effect of a news ban isn’t fewer online page views. It’s that removing reliable reporting from digital platforms will make it easier for uncredible sources to spread lies. The crisis around the Online News Act thus presents a new opportunity to remind readers of our value: to distill, edit, and fact-check complex information at a time when it’s hard to know who and what to trust.