J J Osuna Caballero/Getty Images

A Baghdad battery is not a brand of car battery you can grab off the shelf at your local auto parts store, but the story surrounding these so-called bygone “batteries” is as perplexing as trying to ferret out why your car won’t start.

Four of these 5-inch-tall ceramic jars were initially found inside a grave in 1936, close to where a new rail line was being built at the time. It was also located near what was once the royal city of Ctesiphon, about 20 miles southeast of modern-day Baghdad.

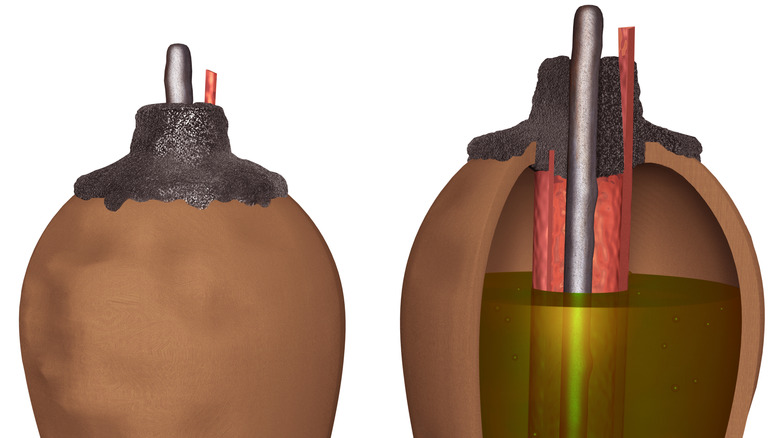

Three contained cylinders made of rolled copper sheets with a copper end soldered to the bottom with lead. One of those had an iron rod inside the rolled copper sheets, with traces of asphalt at the opening, presumably acting like a plug. Similar rods were found strewn about the grave, and all of the jars held remnants of a papyrus-like substance.

Dr. Wilhelm König, a German painter and archaeologist who’d become the director of antiquities at the Iraq Museum in Baghdad, is credited with “discovering” the batteries, but even that accreditation is debatable. Some believe König found them lying in that grave, but others say he stumbled onto them in 1938 while (basically) rummaging around in the museum’s basement.

Establishing the provenance of an ancient artifact — its origin and history of ownership — is paramount to ascertaining whether or not it’s legitimate or a forgery. König didn’t help his case as he never divulged the when, where, or how he found them, further muddying the waters.

The mysterious origin of the Baghdad battery

At the time, König dated the grave to a period when the Parthians occupied the region (248 B.C. – A.D. 226). He firmly believed these jars were batteries because they contained galvanic cells with two different metals having different electro potentials. Furthermore, corrosion inside the jars was composed of an electrolyte (i.e., vinegar or wine); thus, both battery components were present.

With the advent of better scientific methods and carbon dating technology, the timeline has since shifted, and the jars are now believed to belong to the Sasanian Iranian empire (A.D. 224 – 650). Still, it would push back the date of the first recorded battery, created by Alessandro Volta in March 1800, to a much earlier time.

Experiments have shown that when the jar is filled with a weak acid (like vinegar), the “battery” makes about 1 volt of electricity. A General Electric engineer made a replica in 1948 and created almost 2 volts. Some even think if wires were added, it could produce more power, but none were ever found. While humanity’s understanding of electricity is much older than most people realize, calling this a “battery” is a stretch.

[Image by Ironie via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 2.5]

Slicing through the mystery with Occam’s razor

Nik Wheeler/Getty Images

First, an invention like this would have surely resounded across the vastness of the historical spectrum. Yet, there is no written record that such a thing ever existed or was used by anyone — in Ctesiphon or anywhere else. Second, the electrolyte solution would need to be refilled constantly for the device to work correctly, forcing the semi-permanent asphalt cap to be broken each time, rendering it impractical. And given the low amperage, it would take dozens linked together to power anything of significance, which would require wires (that were never found), and wiring technology (that was unknown).

Believers of the battery theory suggest it may have been used to gild or electroplate things, but the electrical output wasn’t powerful enough. Additionally, this method wasn’t recorded anywhere, whereas wrapping things in thin gold foil or using mercury in a fire gilding process were actually used and recorded. To be fair, a German scientist did electroplate a skinny layer of gold onto silver, but he used several “batteries” to do so.

There is, however, a far simpler explanation, one backed by actual archeological records and mentioned by König himself. Remember, these clay jars were found in a grave with a papyrus-like substance inside them. It’s more likely they were used to hold documents for the person once they made it to the afterlife. Other jars similar to the Baghdad batteries were found at archeological digs in Tigris that support this theory.

Perhaps we’ll never know for sure because further study is impossible, as the actual jars were looted and destroyed in 2003 during the invasion of Iraq.