LONDON — Benjamin Abeles’s pioneering research helped power the spacecraft used in some of NASA’s most daring interstellar missions, including the Voyager program that probed Jupiter and Saturn.

But, as a teenager, the renowned Jewish physicist was forced to flee Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia and spent part of World War II working odd jobs and living in air-raid shelters in London.

Abeles’s life and scientific achievements were marked at a June 13 event at the University of Southampton, in the south of England, to which his family has donated a treasure trove of photos, letters and documents.

Abeles, who died at the age of 95 in December 2020, worked for 53 years as a physicist in New Jersey. Together with George D. Cody, his research for the Radio Corporation of America developed the germanium-silicon alloys used in radioisotope thermoelectric generators, which power spacecraft and probes.

Dr. Charlie Ryan, associate professor in astronautics at the University of Southampton, said in a statement to the press that Abeles’s work has had “a very significant influence on space exploration.”

Get The Times of Israel’s Daily Edition

by email and never miss our top stories

By signing up, you agree to the terms

“He helped to develop a type of power source for spacecraft, using radioactive decay to produce power, which is the power source of choice for space missions where using solar panels is not feasible,” Ryan said.

“It has been used on some of the most groundbreaking missions ever launched, such as the Voyager probes that have explored the outer solar system and beyond,” he added.

The technology Abeles helped to develop is still in use today, powering the Perseverance rover currently being used by NASA to explore Mars.

Always an outside

As Abeles’s second wife, Helen, explained at the University of Southampton event, a theme of her late husband’s early story was “being washed along by the tides of history.”

Born in Vienna in 1925 as Bedrich Abeles to an Austrian mother, Selma, and Czech father, Ernst, Ben Abeles spent his early life in Poland, where he later remembered the assimilated family experiencing antisemitism. But the fallout of the Great Depression forced his father, a businessman, to move the family to Prague where he had connections. Although he formed a close circle of friends, as a Polish-speaking Jew, young Ben felt something of an outsider.

In March 1939, Abeles witnessed the German troops occupying the Czech capital. Four months later, his parents waved their son goodbye as he joined a Kindertransport bound for the UK. The rescue effort allowed 10,000 mainly Jewish children to seek refuge in Britain, albeit under stringent conditions. Abeles’s uncle Charles, who paid the £50 guarantee the British government required for all children, was later murdered at Auschwitz with his family.

Abeles did not get on at the boarding school in England to which he was first sent and spent the early years of the war working in kitchens and often living in underground station air-raid shelters.

Although many Kinder found themselves in loving, caring homes in the UK, the voluntary, largely unmonitored scheme also lent itself to cases of indifference, exploitation and abuse.

Abeles’s treatment in the UK at times was thus “not untypical,” Tony Kushner, professor of history at the University of Southampton, told The Times of Israel. “He wasn’t treated always with great respect. He managed to survive, which showed enormous resilience as an adolescent and then young man having to make his own way. He lived a life on the margins.”

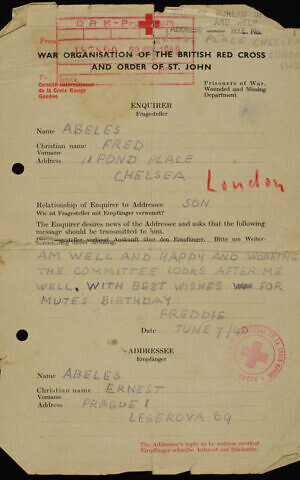

At first, Abeles was able to write to his family back in Prague. A short, telegram-style letter to Ernst from September 1941 contained in the archive reads: “Am healthy. Working in kitchen. With Stefan’s help perhaps opening little snack bar. Love to you.”

One of Ben Abeles’s telegram-style letters to his parents. He was given the nickname Fred in the UK. (Courtesy Ben Abeles Archive)

The importance of the letters to her late husband was underlined by Helen Abeles. “Ben moved around a lot during the war, but through all that time he kept these letters with him. That tells us how precious they were to him,” she said in a press statement. “Ben always said his parents were the real heroes. They were the people that gave him life twice, by making the impossible decision to send him off on the Kindertransport.”

A last, December 1941 communication via Red Cross forms contained the news that Abeles’s older sister, Mary, had married. The archive contains her wedding photo as well as other family pictures dating back to the late 19th century which were safeguarded by a Christian relative during the war.

But, after that telegram, there was silence. Abeles never heard from his parents or sister again. He later found they had perished, together with his brother-in-law, Jan, at the Trawniki concentration camp in Poland.

Brothers in arms

About to turn 18, in May 1943, Abeles enlisted in the Royal Air Force’s 311 (Czechoslovak) Squadron as a ground mechanic. It gave the young man both a feeling of belonging and the encouragement to finish his education. By the time the war ended, he had gained his school matriculation certificate.

Ben Abeles’s sister Mary and her husband Jan Winter on their wedding day in Prague. They can both be seen wearing yellow stars marking them as Jews. They both died at the hands of the Nazis in 1942. (Courtesy Ben Abeles Archive)

After the war, Abeles returned to Prague and, on discovering his best friend from school, Marcel Neumann, was still alive, decided not to go back to London, where a place at university awaited him. Instead, he earned a master’s in physics at Charles University.

But Abeles’s settled and happy existence — he had been virtually adopted by the Neumann family — was to be disturbed by political upheaval once again when the communists seized power in 1948. Rising antisemitism and fears that he might be targeted because of his links with the West led Abeles to emigrate to Israel, where he earned his doctorate from Hebrew University.

However, Abeles’s time in the fledgling Jewish state proved short-lived: he struggled with learning a new language and couldn’t stand the extreme heat. In 1956, he headed for New Jersey.

Abeles’s post-war journey — from the UK to Prague, Israel and then the United States — was “curious,” said Kushner, but not “not untypical of the curious routes that many Kinder took.” Probably less than half of the child refugees, for instance, remained in Britain, which was “not accidental in that the UK was seen as a temporary place of settlement for them,” he said.

Two years after arriving in the US, Abeles met his first wife, Ann, a refugee from Vienna. The couple had three children and remained married until Ann’s death in 2007.

In a March 2021 obituary, his son, David, recalled: “Dad enjoyed exploring the outdoors, and during heavy snowfalls in New Jersey would take out our cross-country skis. I would follow him through the streets, trying to keep up.”

He continued: “An avid lover of hiking and mountains, with his beret, decrepit boots and his eternal outsider mentality and humor he was, for me, Charlie Chaplin redux.”

Abeles met his second wife, Helen, the following year and decided, at the age of 83, to relocate to the UK to live with her. He returned to Britain in 2009 almost 70 years to the day after he arrived as a teenager from Prague.

Late-life activism

Later in his life, Abeles’s thoughts turned often to the suffering his family had endured during the Holocaust, his widow said at the event. He told her that he thought about it every day.

Beyond this searing experience, Helen Abeles said, the impact of the Kindertransport on her late husband was profound.

“The immense sacrifice of his parents in sending him away drove the hitherto bad student and difficult teenager to make something of himself,” she said. “This drive was what enabled the world to benefit from his and George Cody’s generator for space exploration.”

It also shaped his attitude towards migrants and refugees, Helen Abeles believes.

“The experiences of being a refugee and a migrant and the close personal proximity to the horrors of racial persecution gave Ben a huge social conscience and questioning of oppressive political stances,” she said.

In the UK, he volunteered as a translator for newly arrived Roma families from Slovakia and campaigned with charities for safe legal routes to Britain for young refugees.

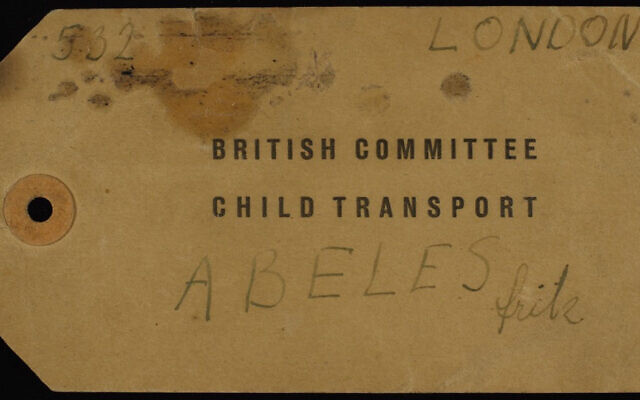

The tag that was placed around Ben Abeles’s neck as he boarded the Kindertransport in Prague, 1939. He was known as Fritz as a child. (Courtesy Ben Abeles Archive)

Abeles’s family has given his archive to the University of Southampton’s Archives and Special Collections, home to the Anglo-Jewish Archive. One of the largest Jewish archives in Western Europe, it comprises more than 4 million items.

The archive spans Abeles’s life: among its items are the tag that was placed around his neck as he boarded the Kindertransport and the Stuart Ballantine Medal from the Franklin Institute in the US awarded to him 60 years later in recognition of his scientific research on the thermoelectric generator which allowed mankind to explore outer space.

Ben Abeles, right, receiving the Stuart Ballantine Medal from the Franklin Institute in 1979. (Courtesy Ben Abeles Archive)

It is understandable, Kushner said, that the lives of high-profile refugees such as Abeles are held up as examples of what migrants contribute to their new homelands. But, he cautions, that alone should not drive why countries take in those fleeing persecution.

“Refugees come in all sizes and shapes. Most of them live very quiet, ordinary lives,” he said. “There is some evidence that refugees tend to over-achieve in the sense that they have to make new lives for themselves, that they are very keen to integrate and be part of society and therefore sometimes their contribution is out of proportion.”

But Kushner said, “That’s not the reason for doing it. We shouldn’t expect it of every refugee. The bottom line is we take them in because it is the right thing to do. Anything else is a fringe benefit.”