Generative AI narrative platform Hidden Door made its grand debut at the PC Gaming Show earlier in June, and debuted to what you might describe as a rough crowd. The rest of the broadcast—dedicated to promoting everyday games found on Steam or the Epic Game Store—was filled with long-running comedy bits mocking the output of tools like Midjourney and ChatGPT.

It wasn’t the best of venues for Hidden Door to debut at. The whole thing felt like watching a standup routine about how much Boston sucks when the opening act was a guy with a Southie accent. Oof.

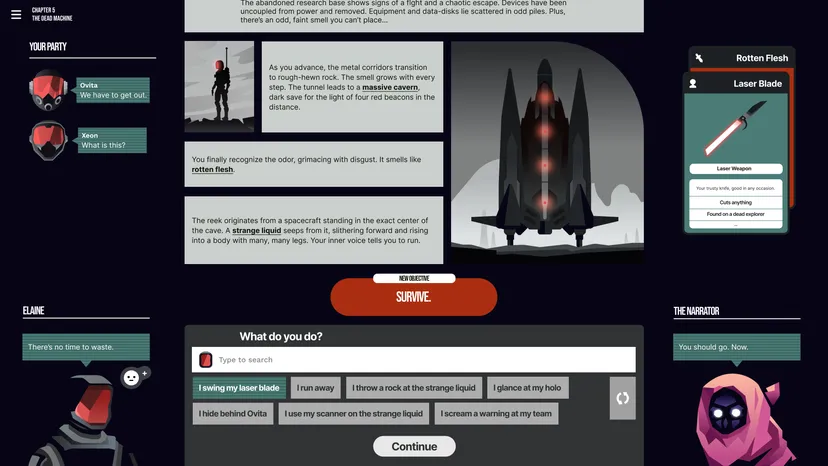

Despite the rough landing there was still something compelling about the pitch from developer Hidden Door (the developer and game share the same name). It’s a tabletop RPG-inspired platform built on top of finely-tuned large language models (LLMs) that doesn’t show any of the red flags that have worried me about other generative AI technologies.

Its creators say they have no intention of replacing or underpaying writers. Hidden Door is assembled from a mix of models that seem to reduce the plagiarism problems plaguing ChatGPT. Maybe most importantly, it’s being pitched with a hype level appropriate to the product. It’s a charming way to play random adventures with your friends, not a step on the path to computer-generated intelligence.

In an interview a few days after the PC Gaming Show, Hidden Door CEO Hilary Mason seemed fully aware of the distrust toward generative AI that fueled the show’s humor. And she had a perspective on the many controversies over the technology that put it in a compelling perspective: that the anger over AI tools doesn’t seem to be about the technology itself, but the value it generates and who will actually benefit from it.

Hidden Door’s CEO has been experimenting with machine learning for over a decade

Mason’s background as a game studio founder gives some helpful context for her perspective on the controversy. As she explained at the MIT Gaming Industry Conference’s AI panel a couple of months ago, she spent years as a data scientist, working on different machine learning-informed technologies that eventually led her to the world of video games.

She also joked at that panel that her first company was spun out of a DARPA-funded research project where she “violated World of Warcraft‘s terms of service to access real-time behavior data on player intent.” It’s an almost perfect anecdote for this conversation about generative AI—an industry built on the ruthless pursuit of data, acquired either with disregard for the data owners or just out of an obsessive belief that data should be free.

Mason seemed slightly chagrined when I resurfaced that anecdote and asked how she’d describe the gap between her thinking about data safety then and now. “For one thing, I was in my twenties and was very adventurous,” she responded. “For another thing, we were in a model of building machine learning systems that in no way would ever compete with whoever was creating the underlying data. That’s been a norm in the field for 20 years.”

“Only now are we at the point where we’ve scaled the ability of those systems to compete directly with the people creating the underlying data, and it’s kind of an ‘oh shit’ moment for a lot of folks.”

She said she’d personally “grown and matured” since those heady World of Warcraft days and would not advocate for the same approach today.

Her comment about machine learning systems “competing” with those who created the data captures the anxiety about generative AI in the market today. Tools like MidJourney and ChatGPT were built on open source academic datasets which scraped internet content under the promise it was for research only—only to then pivot to a for-profit business model to scoop up venture capital cash.

Acknowledging that competition is what helps Mason’s argument take shape: generative AI tools can generate financial value. And the fights over its use—whether in game studios, in the Hollywood writer’s strike, or in education—are about who benefits from that value.

“That’s really the fundamental discussion,” she explained. “Frankly, a lot of things have been set up to squeeze creative folks over the last decade, and now you have this new thing that is competing directly with them by using their work without permission, which is particularly rage-inducing.”

After years of building machine learning-adjacent products, Mason doesn’t view the technology as “innately problematic” but agrees that how the tech is being used and who is benefiting from it directly drives the emotions behind the PC Gaming Show’s presentation.

As for who benefits from Hidden Door—the plan is for authors and creators working with the platform to be paid for their work and for any creations inspired by their worlds to be “additive,” not a replacement.

What is generative AI even good for in games?

Mason was also able to share insights into how generative AI technology might be useful in the world of game development. She acknowledged that the bulk of the conversation has been about slotting generative AI tools into existing pipelines just to make traditional games at a faster, bigger scale.

But she’s been personally interested in building new kinds of games—games that can only exist on the back of a large language model. I asked why she started a company targeting the consumer market rather than a tool developer for studios, since the latter seemed to be a surer business bet.

“My personal view is that the right way to build an amazing product is to own the whole [tech] stack,” she replied. “It’s also the most ambitious way to understand if [your idea] is a great experience, and it’s the only way to be able to build something that is a new kind of experience.”

In fact, it’s worth spotlighting how Mason realized her machine-learning experiments could make for a fun game. Mason’s last company, Fast Forward Labs, had been making machine learning-based text tools for enterprise clients. Think automated customer service chatbots, data summary tools for commodities traders, and tools that could summarize news stories.

These are markets where it’s very important to produce accurate data—and machine-learning tools frequently don’t do that. “It was very clear that…the way these models hallucinate and predict [incorrect facts] is a liability in this sort of environment. But to me, there were tremendous possibilities in opening up creative tooling.”

Mason wanted to stress that by “creative tooling,” she doesn’t want to give the impression that these tools can themselves be creative. Just that there might be a way they can reduce friction on creative projects.

The path from “hallucinations” to “fun game” is interesting because it spotlights an unspoken element of so many weird hype-driven AI projects. The venture capital world is obsessed with the idea of generative AI tools being used to replace conventional media production methods. But it doesn’t seem very good at that, and the promise that it one day will be ignores the underlying flaws of the technology. (Ever notice that Midjourney art doesn’t display a lot of guns? It’s pretty bad at rendering guns).

But while these tools are bad at simulating the real deal, they’re great at producing uncanny images that your brain immediately clocks as “wrong” while looking hauntingly beautiful. It’s too bad that beauty is conjured on the back of scraped artwork.

Mason did want to stress that these tools also have a multitude of safety issues since generative AI tools are weighed down by the biases of their makers and can’t inherently identify when they’re displaying inappropriate or harmful content. The need for safety parameters helped tighten the product that would become Hidden Door.

“We started with an architecture designed around safety and controllability, and we realized that gives us both the ability to provide our players with a safe experience and the ability to work with authors and creators to provide them the controllability,” she explained. She also noted that the generative text models aren’t good at creating story arcs for players—there’s a different system under the hood that’s being tuned to advance rising tension and help players stay on a fun adventure.

Hidden Door’s safety parameters also gave us a chance to talk about the risk of trusting an AI narrator to tell stories set in darker or more violent settings. Mason pointed out that you can’t get the platform to use the word “Nazi” by default (to better avoid white supremacy from creeping onto the platform), but said if someone were trying to make an Indiana Jones-style adventure where the players are punching Nazis left and right, that word could be allowed in specific contexts.

But players in tabletop-type setting sometimes want to explore the darker or more sensual parts of the human experience (just ask my old Dungeons & Dragons party who kept trying to seduce every enemy the GM threw our way). Would those players be able to push those boundaries on Hidden Door?

“We let our creators and our authors whose IP we’re adopting set where they want those boundaries to be,” Mason said. There are types of content the platform would never consider supporting (like sexualized content involving minors) but Hidden Door’s goal is, again, to try and let the creatives decide where the boundaries of the story are.

Even with a copyright-free world like Frank L. Baum’s The Wizard of Oz (the inspiration for the game’s current playable story world), Mason said her colleagues had to tackle some relevant player questions. “Someone asked me in our Discord server the other day if they could kiss Glinda the Good Witch,” she said. Her first reaction was, “Well you could, but she (Glinda) might not like that.”

The company’s solution there was to allow the kiss but put hard boundaries on describing such a romantic encounter turning sexual.

Calling it “AI” helps corporations distract from prospective labor theft

Mason raised some other interesting points about the “value” created by generative AI—and that even the shorthand of calling it “AI” can be a way to obfuscate the real economic impact of the technology by invoking the threat of fictional all-consuming AI beings like Skynet, SHODAN, Lore, etc.

She doesn’t see the technology she’s working with as being anything that could lead to computer-generated intelligence and even tried to give the technology a different name at her prior company. “I fought valiantly to use the word ‘machine learning’ and not ‘artificial intelligence,'” she recalled. “I tried ‘machine intelligence’…but the market didn’t go with me.” (Whatever hesitance she had, we should note that Hidden Door’s marketing goes all-in on the power of “narrative AI”).

But her reluctance about the phrase is validated by the apocalyptic conversations pushed by OpenAI CEO Sam Altman and chief Twit Elon Musk. “I find that conversation is often distracting from the real harms of scaling these systems and the economic disruption [they cause],” she observed. “I’d personally encourage folks to focus on the moment we’re in and the impact on labor markets, the impact on different jobs, and how we think about distributing the benefits fairly.”

Hidden Door‘s debut at the AI-dunking PC Gaming Show captures the strange moment we’re sitting in. There’s legitimate anxiety about how generative AI robs artists to create value for corporations. There are also toolmakers and developers working to understand the real strengths and weaknesses of the technology.

One doesn’t outweigh the other, but if the harm generated by generative AI technology continues, hostility toward more everyday uses of it might equally rise.