Scientific American tech editor Sophie Bushwick explains how Iran is using surveillance tech against vulnerable citizens.

[The above text is a transcript of this podcast.]

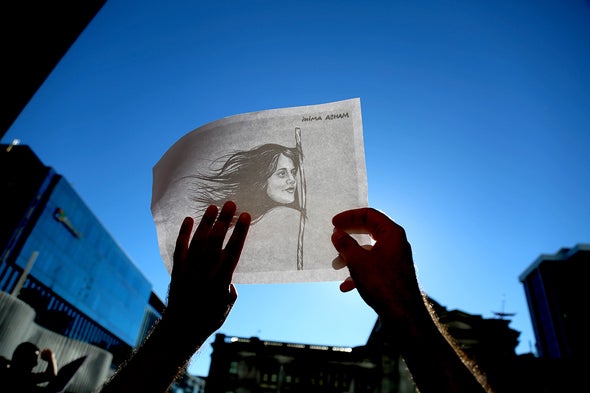

Tulika Bose: This is 60-Second Science. I’m Tulika Bose. Iranians have been fiercely and relentlessly protesting against their government. This was sparked by the death of a 22-year old Kurdish woman named Mahsa Amini who died in the custody of the country’s “morality police.” The demonstrations have been led by young women, who refused to accept restrictive laws like hijab requirements, but authorities have been cracking down with violence, arrests, and with surveillance. I’m here with Sophie Bushwick, our tech editor at Scientific American. Sophie interviewed Amir Rashidi, who is the director of digital rights and security at Miaan Group, an Austin, Texas based advocacy organization working to improve human rights in Iran.

Bose: Hey, Sophie.

Sophie Bushwick: Hi. Sophie.

Bose: So how did you find this story?

Bushwick: I had heard that some protesters in Iran were worried about the government using facial recognition. And I reached out to Amir to just ask them about this technology in particular, but what I learned is that the use of technology for suppression in Iran goes way beyond facial recognition. In fact, the government is actively trying to create its own nationwide intranet that would be separate from the global Internet and allow it to maintain much stricter control over what its citizens can see on the internet.

Bose: Do you think that has any ramifications in the near future?

Bushwick: So within Iran, what I learned is that the government has been interested in this intranet project for a while, but there hasn’t been a lot of adoption, in part because people know that the government is really interested in surveillance and censorship. It’s not just a matter of creating their own servers, they need their own data centers, and they need their own proprietary apps. They’ve shut down access to WhatsApp, they don’t want people to be communicating with the outside world or to have access to that kind of information. So what they’ve instead suggested is they’re trying to push citizens to adopt nationwide apps, and the nationwide intranet. They’ve done things like making the nationwide intranet cheaper and faster than accessing the global Internet.

Bose: Is Iran taking a page out of anyone else’s playbook here?

Bushwick: Yes, there are a lot of authoritarian governments that are very interested in the use of technology for surveillance and censorship. In particular, Iran has a technology sharing agreement with China. There’s a category of apps called Super apps. So an example is WeChat, which is a Chinese app where you can, you know, stream, your favorite videos, you can buy tickets, you can chat, you can browse the internet, it’s one app that sort of encompasses the whole world of apps that smaller apps might focus on. And there are apps in Iran that are attempting to do the same thing. So the problem with this is that if you, for example, get kicked off of that app, you lose access to your life. Another thing is that if that app is controlled by the government, or by a tech company that is willing to do whatever the government says, then they can have very quick access to everything that you’re doing online. The concept of having a country wide intranet, instead of using the global Internet is not exclusive to Iran, either. Russia announced that they wanted to do this, although they haven’t actually implemented it on a on a completely closed basis. It’s becoming clear that multiple authoritarian countries want to have their own little islands of internet that would be separate from the global Internet.

Bose: That sounds pretty terrifying.

Bushwick: It’s not great. It’s not great for people who live in the countries that are controlled by the government. And it’s not great for people who, who believe in the concept of the internet as a unifying source where people from all over the world can connect with each other and read about what each other are doing.

Bose: Aside from being shut off from like the global internet, what else could happen?

Bushwick: Recent reporting actually suggests one of the ways that the government might be throttling connectivity speeds, at least for cellphone users. And that’s a computer tool called SIAM. Telecommunications companies install it and it basically gives the government the ability to target internet speeds on individual’s phones. It’s even scarier than that. It has other surveillance access to phones, so it could track a phone’s location, it might be able to decrypt messages and other information. And in general, it seems like a surveillance tool that telecommunications companies are just handing over to the Iranian government.

Bose: What do you think the biggest takeaway is from this story and what should people know going forward?

Bushwick: Governments that will want to control their citizens are learning from each other. But internet freedom activists are also learning from each other and advocates all over the world are trying to help Iranians. They’re trying to increase access to the internet and that they are also learning from each other. And I think one of the things that illustrates is the value of the global internet the way it allows people from all over the world to connect on a common on a common cause.

Bose: Thanks for listening to 60-Second Science. I’m Tulika Bose.

Tags:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

Sophie Bushwick is an associate editor covering technology at Scientific American. Follow Sophie Bushwick on Twitter Credit: Nick Higgins

Tulika Bose is senior multimedia producer at Scientific American. Follow Tulika Bose on Twitter